Today, I am thrilled to bring you an interview that I did with Anna Gifty. Anna is a PhD student at Harvard in economics and public policy. She’s an author of The Black Agenda, which is what we’re going to talk about today and of the Substack newsletter, A Seat at the Table. In 2018, she co-founded The Sadie Collective, which is the first nonprofit organization to address the underrepresentation of Black women in economics, finance, and policy.

Anna is someone who I really admire and have felt very privileged to get to know in the past few years and privileged to call her a friend. This was a really interesting thought-provoking and fun conversation, and I hope you will listen and enjoy. We also have an excerpt from The Black Agenda that’s published in the newsletter, so please head over there to check it out after you listen to this. And now to my conversation with Anna.

So I am delighted to welcome Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman to the podcast. So first I want to say just thank you for being here. I’m extremely excited for this conversation. Our goal here is to talk about your book, the Black Agenda, which is out in paperback this week, and which I hope everyone will read. I read this book when it came out a year or so ago, and I really read it as a kind of call to action to bring diverse perspectives and in particular perspectives of Black scholars into our policy debates. The book really covers a huge range of policy issues, and I actually want to start by asking you about that choice, although we’re going to focus our conversation mostly on the essays about education and representation. But before we get into that, I would love if you would just introduce yourself.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Well, first of all, thank you so much for having me, Emily.

Emily Oster:

I feel like I should tell everybody that I really like you and we’re friends, and I think we’re friends.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

We’re friends, yeah.

Emily Oster:

And so outside of the formality I’m just delighted we get to talk.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Thank you. Yeah, no, it’s great to be here. We’ve known each other for a while now actually, which is really awesome. I think very early on when I entered economics as a student, we got to know each other really well, and it’s been awesome just seeing this platform grow and seeing this community grow. So again, thank you so much for having me on. So hi everybody. My name is Anna. So my official name is Anna Gifty, but most people call me Anna. And currently I’m a PhD candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School where I study public policy with the concentration in economics.

And so the topic I typically focus on deal with sort of the intersection of race, gender, and class as it pertains to the workplace, but also broader economic trends. And so this book kind of pays homage to the individuals who sort of laid the foundation for the work that I’m hoping to add on to, but also it’s kind of an extension of the things that I want to learn more about and also the conversations I’ve had with individuals such as Emily around topics that need more Black expertise to be infused into the conversation so that we can start to really address the heart of problems and kind of build solutions in a way that actually serves us all.

Emily Oster:

So the book is a collection of essays, and it is on an enormous range of topics. And I want to ask you about that because I think to play devil’s advocate by having these all live together, there’s a potential dilution of the individual messages. And I actually read there as a sort of broader point, but maybe you could tell me why you put this all together.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah, that’s such a great question and point to make, I think. So these essays talk to one another. I think that you can read these essays out of order, but what you’ll realize after reading about two or three of the essays, even if they’re not in the same chapter, is that they are in conversation with one another. The big idea that this book is trying to present I think, is that if we’re trying to solve problems in our community, we can’t ignore Black people. That is the overarching message across the board. And then I think that this book takes it one step further where it’s saying, not only can we not ignore Black people, but the solutions that we have to these problems can’t ignore Black people as well.

And so where things vary oftentimes is the kinds of solutions that people present. So I like to talk a little bit about the criminal justice chapter. Criminal justice as a topic and policy issue is highly contested both in media, but also I think in people’s personal circles. People have very strong views on police involvement in communities thinking about the role of the prison system, et cetera. And people have very, very different solutions about that. But I think the overarching message of that chapter and the chapters within the book is that whatever solution we decide can’t ignore Black people because Black people are a big, big part of how this country came to be.

Emily Oster:

Actually, I resonate with all that. I actually think the pieces that I think are most important are when you are in spaces, when the book is in spaces where we wouldn’t be looking for those voices as much. I think there’s some stuff about-

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

That’s right.

Emily Oster:

There’s parts on climate change and you say, “Well, what do you mean climate change?” And I think with that, sometimes there is a frame of we’re going to include Black voices when we are talking about a topic that feels like it has an obvious racial component and criminal justice is in that space.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

That’s an example.

Emily Oster:

Then when we’re going to talk about something else like climate change or environmental justice or, it was, “Well, we don’t need to have diverse voices because we can cover that with white people.” And I think that some of the point of the book is like, “Hey, actually this should be part of all of these policy conversations and it should be overarching and everything.” And I think that’s an important point.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah, I think that’s a really great summary of that point around, I think what Dr. Tressie McMillan Cotton says is there’s race talk, this idea of there’s never really space for Black expertise to just be in the spaces that Black experts reside in. It’s very much relegated to Black History Month, relegated to now Juneteenth, relegated to when we’re highlighting racial gaps in policies and acknowledging those racial gaps like Black Women’s Equal Payday. But the idea here is all throughout the year, every year, Black expertise is really, really important, not just because it’s Black, but because Black people are people too. And so it’s really important to recognize-

Emily Oster:

It’s a great point, Anna. It could be the title of many things.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Right. But that’s really what it boils down to it’s like, “We’re people too,” and so our opinions are just as important. And I think that to some degree, a lot of times when different entities and institutions focus on one group’s opinion as sort of the default opinion, you end up missing out on all these other potential solutions to problems that are facing all of our communities that could actually be really, really helpful.

Emily Oster:

There’s sort of three chapters of the book that I think are most resonant with the audience who listens to this. First, there’s a great essay on maternal health, and we’ve talked a lot about maternal health in this newsletter recently, and so we’re not going to talk about that, but it is a great essay that highlights a lot of the issues that I think have gotten more attention but should get more attention around racial disparities in maternal health. The two that I do want to dig into more, the first is one by Lauren Mims, which is on Black girls. It’s about education, and she makes a point in the essay that Black girls are not sufficiently valued in education and policy and practice, and I almost read her essay particularly at the end as saying that our education system as we have it now, allows for the possibility that Black girls could be exceptional. Scholars allows for the possibility of Anna, that Anna would appear in your school and that would be something you can value, but it doesn’t hold them to that expectation. Is that how you read this?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Wow. So well said.

Emily Oster:

Excellent.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Okay, Emily.

Emily Oster:

I got it. It’s a great essay.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

I love it. Yes. I know I’m not supposed to have favorites. That is my favorite essay in the book. I just think it’s really well written, one, but also I think it kind of blends together the overarching theme of the book and connects the individual experience to the systemic reality. Like to your point, Black women are not valued. Black women and girls are not valued in education. Ironically enough, Black women and girls go to school a lot, so we can’t ignore the fact that there is a subset of our population that is educated and is increasingly becoming more educated and they want to be contributors to our economy and to our country and to the world at large, but there’s a very real rejection to them being in the space. And how does that sort of impact one class dynamic, but more importantly the outcomes of these women and girls as they kind of progress through life.

In that essay in particular, Dr. Mims talks about how she’s specifically teaching a classroom of Black girls that many people would just dismiss. So Black girls who might at times fit some of the stereotypes that people know about Black women that are not always accurate, but in this case, that’s what their experience is about. And how when she asked these individuals to share why they might be in this particular program that she’s teaching, they shout out things that a lot of different voices tell Black women on the daily, you’re not enough, you’re not smart enough. You fit this stereotype, you fit that stereotype. And she tells us, the reader that she’s almost driven to tears. A lot of times when I talk about this essay, I’m also driven to tears because I think on a very basic level, this idea of Black women being disruptive to a classroom setting is real. As someone who was always told that I was too enthusiastic and I needed to use my inside voice nearly every day, right? Now, granted I’m a loud person.

Emily Oster:

Yes. You’re a loud person.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Copy that. But there’s this sort of punishment for expression that varies depending on the kind of culture in the household you were brought up in. Perhaps the way that I display joy is I laugh loudly and I’m trying to make other people laugh, and that’s something that’s ingrained in me based on how I was raised versus perhaps what many would consider how white children, especially white children in wealthy neighborhoods are raised up to be. I think what I love about her essay in particular is it humanizes Black girls in the classroom and beyond, and it kind of gives us a really clear picture of there are some really practical things that we can do to start addressing this problem, including funneling resources and community to these Black girls.

And so that is something that I think it’s really, really important. I mean, I’m talking to a bunch of parents right now, and I think that it’s really intentional that as a parent, especially if you’re not someone who identifies as Black, it’s important for you to recognize that your child might be in a classroom with a Black child or a Black girl.

And if you witness something where that Black girl feels disempowered, I mean, I think it’s important for you to step in and say, “Hey, no, what you’re doing is great,” or further affirming that Black child. There’s research by Joshua Erikson and his co-authors that talks about stereotype threat, right? This idea that a lot of times when people are told about their identity as it relates to some sort of average outcome that’s not favorable. People feel less about themselves and it actually impacts the way that they perform. And so I think it’s really important for educators, for other parents and other members of the community to affirm Black children and to affirm Black children regularly. And so that’s a very practical on the ground thing that I think people can do pretty easily, especially if Black children and Black parents are in your community.

Emily Oster:

The other piece of this that I feel out of that essay is the kind of what is the incentive generated by these kinds of structures to controlling the kinds of behavior or generating a need for conformity, and even to things like dress codes, which she talks a little bit about, like when we have a dress code that whether inadvertently or inadvertently it makes most acceptable a particular set of clothing which is culturally specific or makes unacceptable that, that’s a signal in either directly or indirectly about how should you be showing up here? You should be showing up not with your whole self or with a kind of version of yourself that is…

And actually, I mean, I think I see this to a very different extent in the other space that we share, which is being a woman in economics, and you have an intersectionality aspect of that that I don’t, but even just with the gender piece, I think there is often this pressure don’t show up with your whole lady self, show up with your… I mean, and actually some of the most prominent women in our profession have talked about the idea of wearing boring shoes. You have to wear boring shoes so the men aren’t like, “Ah, there’s a lady with her shoes.” And this of course is a very different space, but the same in some ways a parallel kind of idea about just, well, you can’t be yourself, be a version of someone else.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah, that’s such a great parallel. There’s somebody I grew up admiring and witnessing from afar, kind of expending from Dr. Mim’s essay. So there’s this woman called Bozoma Saint John. Many of you might actually know who she is. Really, really prominent marketing officer, also Ghanaian American, so she’s Ghanaian American like me. And when I was first in college and I first got exposed to her, I noticed that she was incredibly unapologetic. She wore Ghanaian prints everywhere. She was super colorful. Her hair was in an Afro. It was just very much…

The thing is whatever people wanted to assume about her before she opened her mouth, they could, once she opened her mouth, it was like you couldn’t really say anything about her intelligence, her intellect, the way that she showed up. And I don’t know why, but for me, that has actually been something that I’ve started to intentionally do where, you can actually ask my professor, which we both know Larry Katz, when I come to economics, my labor economics courses, I’m dressed to the nines. I look good, right? I’m wearing something nice. I did a little bit of flare.

And I remember Dr. Claudia Goldin also was another professor in the economics department. They’re actually married. She’ll say like, “Wow, you look really nice.” And I’m like, yeah, and then I’ll proceed to ask really thoughtful questions in class. And I think it’s really important to recognize that you can show up as yourself and still be this brilliant, amazing, smart, intelligent, astounding person. You can do those things at the same time. I think the Black women in my life have always said that people sometimes get mad that some of us can multitask ask. And I’m not going to also diminish the fact that there has been in the past and even to some degree in the present, a real cost to showing up as yourself, yourself. So to your point, Emily, around how some of these older women economists had to essentially mimic what it looks like to be a male economist in the profession to get through. That’s real.

I think when we add this element of intersectionality, though, I can’t conform my race, that’s the gag. And so I think that’s a little bit like what Dr. Lauren Mims is talking about, like there’s a very real reality that just comes with how we were born that we didn’t ask for, but we’re getting punished for. And so how do we ensure that Black girls in particular, but more importantly other underrepresented groups, feel empowered in the classroom to then feel the need to empower others? And so I think that it does begin, to your point with sort of normalizing what does it mean to show as yourself and encouraging young children to do that? And I also think that also boils down to how we treat children. There’s a lot of conversation now about people not treating children as humans. I completely subscribe to that conversation.

Sometimes you’ll see people talk to kids like they don’t know anything. But the reality is kids are very, very aware and want to be aware and want to be curious and want to learn more about the world. And I mean, this actually transitions really nicely to our next essay, but limiting kids’ ability to be curious is limiting people’s ability to grow and evolve and eventually improve upon what we already have. And so what you’re seeing now with a lot of these laws that are trying to ban kids from reading certain books is a limit on curiosity at its core. Kids are curious, they’re going to have questions, they want answers to those questions, and sometimes those questions are going to be hard for the adults that they’re asking those questions to. And I think a lot of what we’re seeing right now with bans on books is adults refusing to provide answers to those questions and finding different creative ways, quote unquote, to not answer those questions. It’s this idea of if they don’t even know about it, then I don’t ever have to address it. Yeah,

Emily Oster:

No, and I think I completely agree with all of that, and I think that what is underlying that is that books are, for many kids, I think often a way into questions, into understanding, into talking about topics that are hard, and that could be a good way, ideally I think of that as a good way. But of course, if you don’t want to have those conversations, then somehow we can say, well, if you don’t read the books, and then you’ll never find out about this until… Of course you will find out about it, and that’s not. But that is in fact, a great segue into talking about this next chapter, which is about the value of Black children’s books by Dr. Obiwo and Starks. And we actually did an interview in the newsletter a couple of years ago, even with Anjali Adukia, who’s at Harris about representation in books.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Oh, she’s amazing.

Emily Oster:

They’re quite interesting research on basically the fact that Black characters in the Newbury Award books tend to be lighter skin. They did all this image analysis, which is a whole other thing.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah, it doesn’t surprise me.

Emily Oster:

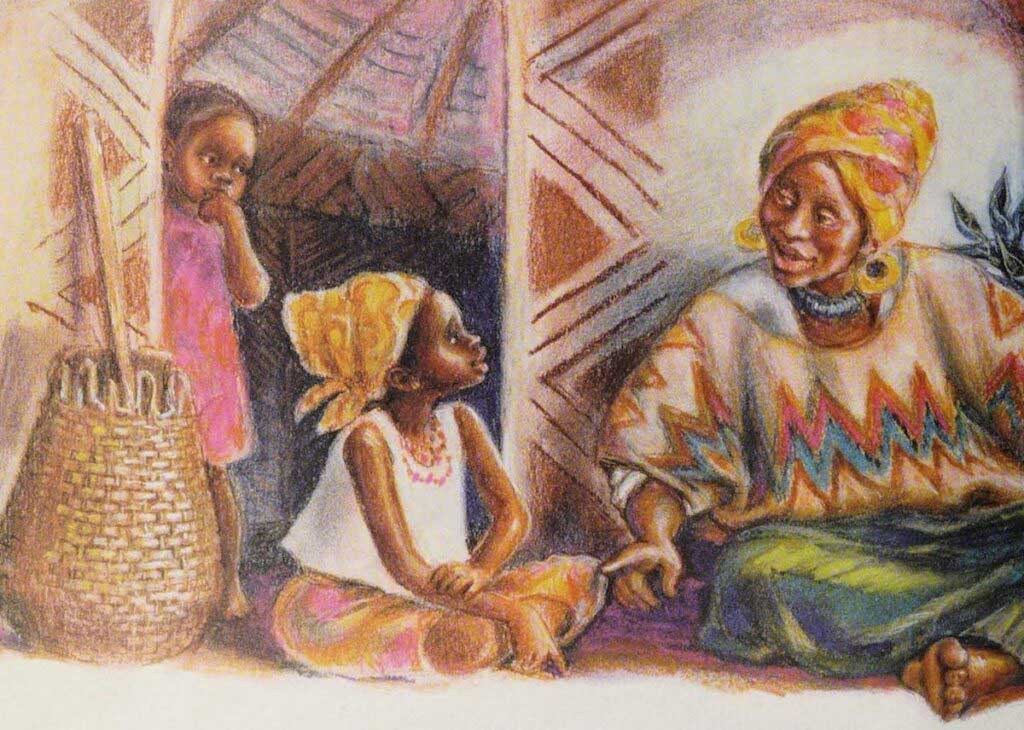

This chapter is sort of about books as mirrors in a slightly different way. Do you want to say a little bit about what you took out of that chapter?

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah. I love this chapter as well, and it’s really, really relevant. My big idea from this chapter is that it’s really, really important that people have access to books with Black characters in it, because books are oftentimes a way for us to humanize individuals that we might not be in close contact with. It’s easier to empathize with somebody when someone gives you a direct look into the way that they’re thinking. And books are one way to do that. I think when we look at children’s books in particular, a lot of times images are made really salient to young people when they’re exposed to them. I mean, I don’t know what the research is on that, but this idea of when people read picture books… I remember the picture books that I read back in the day, right? That one with the mouse and the cookie.

Emily Oster:

Yeah. You give a mouse a cookie and that’s it. There’s like old sequel. That guy really milked that. I mean, it’s like-

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah, he did.

Emily Oster:

… for the mouse and the cookie, and then it’s just all the other animals with different desserts.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yes. That’s right. Or even if it’s not even a picture book, but it has a really important visual image, and you kind of get a sense of what people are thinking, like Junie B. Jones, [inaudible] Junie B. Jones, which raised a lot of us. So it’s important for us to hear the voices of Black people in the books that we read, especially for Black children. And what I really love about what they argue in this is that there’s this sort of idea of like, okay, we need diverse stories, sure, but I think the other reality of it is Black children also need to be able to read about themselves, read about what they could become, what they are and what they’ve been. These are all things that are important.

And I think the gag is white children have that privilege. A lot of us grew up reading books centered on white children, Magic Tree House, three white children, Junie B. Jones, a white girl. And there’s nothing wrong with those stories existing, but why do those have to be the only stories to exist? That is the question. And what are we missing from just the whole discourse around the kind of lives that people live if those are the only stories that are featured, right? Because the reality is not everybody is white rich and living in a suburb.

Emily Oster:

I thought you were going to say not everybody is traveling through time in a Magic Tree. I was going to say that’s also true, also correct.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Also true, right? I mean, that’s just the reality of it. And so I think a lot of times too, as somebody who spent her summers reading books to get one free coupon to get a Chick-fil-A ice cream cone, for me books ended up being also a way for me to figure out myself. And the gag is if you aren’t seeing yourself in the stories that you’re reading, it just makes that process that much harder and it ends up being worse off for everyone because I think to some degree, books allow us to feel empowered in our own stories, our own lived experiences, and I think that when people don’t feel empowered, when they don’t feel like they have a grasp of who they are, it can spin out of control in a way that ends up being harmful to other people. And so I think that to me, it’s even preventative, having Black children featured in books, having Black people featured in books, being intentional about the stories that individuals are hearing, and not only limiting it to Black people.

I think Black people is a great place to start, but I think Asian American stories are important. I think Latinos and Hispanics are important to be in stories as well, and all of these groups are very underrepresented in literature, and the question is, why and what are we losing from that? Because the reality is kids are curious about these stories because they’re going to school with people who look like that, and so they want to know more about them.

And so you don’t want to, I think the way I put it is you don’t want to set your kid up where they grow up and they don’t have a good grasp of other people’s stories, and that makes them a worse communicator or worse citizen of the world. You want to make sure that they are equipped in the way that you prepare them for school or prepare them for the workplace. You want to make sure that they’re prepared to be a good person, a good human being to somebody else. And the only way to do that is to expose them to the stories of other people that may not be in their community or may be part of their community, but are in a very different reality.

Emily Oster:

The other piece of it in getting to the point about people liking to read in your experience reading, is we actually know from a lot of research that kids will read more about topics that they are interested in, which of course seems completely obvious, but you got to have research. We got to have something to do. And the way you can see those things, if you give kids in the US a bunch of books about cricket, they won’t really read them because it’s very difficult to understand what’s going on in this cricket game. When you give them a book about baseball or basketball or soccer they’re going to be more interested in it because it’s like you have the context. But there’s an extension of that, which is when I am seeing characters who I identify with, that is a piece of getting engaged in that book.

And I think a lot of the way we expose kids to diverse perspectives in books is very specific, I guess is the word I’m looking for. We read books about Martin Luther King or reviewed books about Malcolm X, we read books about where they’re centering Black people, but not centering the experience of kids who are going to be reading.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

That’s right.

Emily Oster:

So it’s like, yes, these are sort of stories of impressive people that we all should know, but it’s different than Junie B. Jones or it’s different from the Babysitter’s Club or something where that’s my experience that I’m reading about someone who I should be identifying with personally, but so rarely do those characters look like me, or I mean, they actually do look like me. They rarely look like you.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Right. Yeah. I mean, to build on that point, I love what you said there. I think it boils down to Black people are not part of the ordinary. Why? That is just what it is.

Emily Oster:

It’s the same image. It’s the whole point of this essay book in some sense.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

That’s right.

Emily Oster:

Which is-

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

That’s exactly right.

Emily Oster:

… this should just be ordinary. It should not be like we look for this in a special circumstance. It should be that these voices are everywhere.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

That’s exactly right. Then it goes back to this fundamental idea that I think this book is also trying to show that Black people are human too. This idea of being human means you have ordinary experiences. It means that you can babysit kids too. It means that if you want to climb into a tree house, you can do that too. But I think that that’s precisely where the tension lies, this idea that Black people aren’t humans or not seen as human most of the time, and so the Black people that end up being featured are the ones that folks deem exceptional or deem exceptional enough to be humanized or not even humanizing. A lot of times those individuals, the folks like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, or Harriett Tubman are exalted in such a way that they’re still being dehumanized because we’re not really getting the full sense of who they are.

Not to say that those stories that praise their achievements and praise their efforts are not needed. They are 100% needed. But I think that we need Black girls and Black boys and Black children overall who are just centered in the ordinary, and I think we all miss out when they’re not Black children, especially miss out. That’s kind of what this essay is getting at too, and that’s why books like Hair Love by Matthew Cherry is so important. This is a Black girl getting her hair done. We all get our hair done to some degree, but there’s something distinct about the way she’s getting her hair done and it’s ordinary. And so I think that those are the kind of stories that we really, really need moving forward to kind of combat some of the ideas that formed very early on around race and…

Oh, I think there was a study that was featured on CNN, I forgot who ended up doing it, but they brought a bunch of children in. They kind of replicated it, but they brought a bunch of children in. They showed them a bunch of pictures of drawings that varied in shade, and they said, show me the good child. Show me the bad child. Show me the child that you want to be most like. A lot of the Black children chose the white child.

Emily Oster:

It’s like the doll-

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

What does that say then?

Emily Oster:

… the doll experiments as well.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah, the doll. It’s doll experiment. Yeah, I think it was a replication of that. What does that say about… I think for me, if I was a parent, I would be heartbroken by that, the fact that this young Black child doesn’t think that they’re worthy and they’re only five. That’s crazy, right? Because I think as a parent, many folks know that, oh, if that’s how you’re feeling at five, there’s going to be so many more messages that come down your way that are going to try to get you to believe that. And so if you’re already starting there, fundamentally you are already set up for failure.

And so how do we begin to intervene there? This essay says we begin with books. Books are a really good way to begin. And I think with white children in particular, because I’m talking to a lot of white parents here as well, you can disrupt the way your child also thinks about who’s the good child and who’s the bad child by introducing those types of books in your household and ensuring that, I always say it’s going to be kind of spicy, but ensuring that the Black people and Brown people that you engage with are not just people who serve you. Because I think a lot of times people only engage with Black and Brown people when they’re at work, when there’s a clerk that they’re engaging with or if they’re engaging with somebody who is offering them something or serving them. I’m talking about white parents in particular. And I say this as somebody who went to school, excuse me, with white children. I went to private schools growing up on scholarship with a lot of very wealthy white children, and that was their reality.

And so in some ways, me being the space was disruptive because their benchmark was whatever they saw on TV was a flattened version of what it meant to be Black. And I was this three-dimensional person in their mist who kind of got upset sometimes, who vibes sometimes who could relate to them sometimes. And for a lot of them, I think, and I know at least for one, me being there, helped them rethink the way that race showed up in their life. And so I think in a very real way, you can start that process by introducing Black people, Black children in the ordinary at a very, very young age.

Emily Oster:

I feel like I talked to you for nine hours, but-

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Yeah, that was actually really good.

Emily Oster:

… this is awesome. Okay. You’re great. Listen, before we end, tell people where they can find you and what you’re doing next.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

So where can you find me? One, Emily doesn’t know this, but I’m about to say it. I restarted my Substack.

Emily Oster:

Oh, Substack. Amazing. Okay.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

I’m back. I’m back. So it’s just annagifty.substack.com and it’s called A Seat at the Table. So if you’re interested in topics like these or you want to learn more about them, this is essentially going to be a Substack that provides a digest on things related to identity, policy in the world around us. And so I’ll be sharing what I’m reading, what I am rethinking, and what I’m researching around these different topics, and also sprinkling some memes if that’s the thing that you’re kind of into. But I’m also on social media as well. I’m pretty actually engaging there too, so I’m happy to talk to folks who want to answer or ask questions. Sorry, ask or answer questions around the topics that we’ve discussed today. So everywhere I am Itsafronomics, I-T-S-A-F-R-O-N-O-M-I-C-S. And yeah, that’s kind of where you can find me, Twitter, Instagram, and then I’m on LinkedIn if you’re a business type of person and you want to connect with me there. But thank you so much. Yeah, I’m excited to connect.

Emily Oster:

Yes. Thank you so much for doing this, and yeah, thank you. I will. Thank you. Thank you. We love you.

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman:

Thank you, thank you, thank you. I appreciate you.

Emily Oster:

Thanks for listening. If you like what you heard, subscribe to ParentData in your favorite podcast app and rate and review the show in Apple Podcasts. You can subscribe to the whole newsletter for free at www.pdstaging24.wpenginepowered.com. Talk to you soon.

Community Guidelines

Log in